I had the rare opportunity of an evening out last night and headed down to Fibbers (one of York’s most palatial and salubrious night spots) to see Blackbeard’s Tea Party. Anyone who lives in York will probably have seen them busking in town; but this was one of the first chances to see them headlining– also to see them wired up rather than entirely acoustic. After a couple of support act (some drumming gubbins and a bloke and a guitar) they hit the ground running with British Man of War. One of the great things was that this was a proper gig with a proper atmosphere. Much as I like folk music, occasionally the atmosphere can be a bit ‘Sunday school teaparty’ – I remember once being told off for talking during a Dhol Foundation gig at the Beverley Folk Festival- apparently I should have been sitting down quietly. Anyhoo, it was their usual mix of songs and tunes (often with a nautical theme) with electric guitar and bass adding a bit of oomph (as did the sousaphone). Highlights for me were Rolling Down the River and I Can Hew. All in all, a good night out – looking at their MySpace page they appear to be putting in an appearance at the Beverley Folk Festival this year and they’ve already been played on the BBC2 Folk programme with Mike Harding. Now if Fibbers can only do something about the price of their beer….

I had the rare opportunity of an evening out last night and headed down to Fibbers (one of York’s most palatial and salubrious night spots) to see Blackbeard’s Tea Party. Anyone who lives in York will probably have seen them busking in town; but this was one of the first chances to see them headlining– also to see them wired up rather than entirely acoustic. After a couple of support act (some drumming gubbins and a bloke and a guitar) they hit the ground running with British Man of War. One of the great things was that this was a proper gig with a proper atmosphere. Much as I like folk music, occasionally the atmosphere can be a bit ‘Sunday school teaparty’ – I remember once being told off for talking during a Dhol Foundation gig at the Beverley Folk Festival- apparently I should have been sitting down quietly. Anyhoo, it was their usual mix of songs and tunes (often with a nautical theme) with electric guitar and bass adding a bit of oomph (as did the sousaphone). Highlights for me were Rolling Down the River and I Can Hew. All in all, a good night out – looking at their MySpace page they appear to be putting in an appearance at the Beverley Folk Festival this year and they’ve already been played on the BBC2 Folk programme with Mike Harding. Now if Fibbers can only do something about the price of their beer….

(In the interests of full disclosure I should say that Laura from BBTP is my fiddle teacher )

London 2012 Opening Ceremony

I watched the Winter Olympics opening ceremony a few weeks ago. A typically brash and overblown celebration of the culture of the host nation. Obviously my thoughts now turn to what delights the London Olympics opening ceremony will deliver, and what aspects of British culture will be involved (cardigans? pot noodles? mild disappointment? out-of-town shopping centres?). Personally, I am fully supporting the campaign to see Morris Dancing included. I kind of like the idea of 14,000 choreographed morris dancers performing in perfect unison, in some kind of bastard mix of the Archers and totalitarian mass callisthenics.

I watched the Winter Olympics opening ceremony a few weeks ago. A typically brash and overblown celebration of the culture of the host nation. Obviously my thoughts now turn to what delights the London Olympics opening ceremony will deliver, and what aspects of British culture will be involved (cardigans? pot noodles? mild disappointment? out-of-town shopping centres?). Personally, I am fully supporting the campaign to see Morris Dancing included. I kind of like the idea of 14,000 choreographed morris dancers performing in perfect unison, in some kind of bastard mix of the Archers and totalitarian mass callisthenics.

I’d also like to suggest a new Olympic event. As most people know, the marathon is traditionally believed to have been based on the run made by Pheidippides from the battlefield of Marathon to Athens to report the Greek victory over the Persian in 490BC. If we can base sporting events on Greek historical events, then I think we should be able to use British history as a source for unique races for the London Olympics. In 1600, Will Kemp, an actor and jester known for taking comic roles in some of Shakespeare’s plays, took 23 days to morris dance from London to Norwich. He later published a description of this event called the Nine Days Wonder. Thus, I’d like to suggest the 186km prance as a new event for London 2012 – the winner to be awarded a gilded pigs bladder.

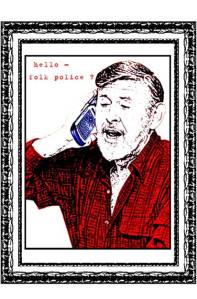

Nick Griffin – folk music fan!

Last weekend’s Guardian had a fun piece about the music favoured by dictators and political villains (Robert Mugabe is apparently a fan of Cliff Richard whilst Mahmoud Ahmadinejad favours Chris de Burgh). However, there was little bit of the article that mildly pissed me off. Amongst the pantheon of bad hats and loonies was Nick Griffin,who apparently is a fan of (and I quote) “that most arthritically white of genres”, English folk music including ‘nu-folk poster girls Eliza Carthy and Kate Rusby’. According to his blog Griffin finds it ‘”an alternative to the multi-cult junk played incessantly on Radio 1″

First of all, a slap for the journalist for that lazy bit of stereotyping and secondly a slap for Griffin (I don’t think I need a reason for that). I’m sure they’ll both be pleased to hear that Eliza Carthy is currently touring in the band Imagined Village, whose members include a sitar player, one of the country’s leading dhol drummers and an overall line-up which is about 50% ‘non-indegenous English’. I saw them live in Leeds at the Irish Club on Tuesday (I’ll post a review soon). Pleasingly the band had also picked up on the article and videoed the entire audience flicking the Vs at Griffin and shouting “bollocks”; they are doing this at each venue on the tour and will be editing it all together and putting it on there website as a suitable rejoinder to the BNPs attempt to get into folk music.

Does this matter in the big picture of things? Well, lets face it, I don’t think that all Nick Griffin needs to do to make the elusive electoral break-through is to profess an appreciation of Steeleye Span and The Wurzels; nor, I suspect, will the SSuporters of the BNP be particularly dismayed that a bunch of weirdy beardy folk fans don’t like them. I still think its important though to try and attempt to resist Griffins/BNP attempts to annexe English folk music, history, archaeology and other things close to my heart in his rather half-arsed attempt to create a volkish image of an indigenous national culture which he is trying to use to contest his (mis)-understanding of the multi-cultural society we actually live in. So, if shouting “bollocks” to Nick Griffin and his nasty little party are what we have to do, then so be it!

(Image whipped from David Owen’s Ink Corporation website; an excellent site well worth looking at).

Woolworths and Leylines

The Guardian’s always excellent Ben Goldacre strays into the world of archaeology with a nice piece on the latest claims about the sacred geometery of the prehistoric world – also worth reading for the comments below. The work in question claimed that prehistoric monuments were so arranged as to form a network of triangulated points that were used by past societies to navigate around the country. It also reports a counter analysis that showed that similar patterns could be found in the spatial distribution of Woolworths

The key point, of course, is not whether prehistoric societies ritualised their landscapes through monument construction (something accepted by all mainstream and ‘alternative’ archaeologists), but how data is used and analysed. Like any study which involving recognising patterns in huge amounts of data, it never really confronts the fact that if we have enough points of data (whether these are inscriptios, Bronze Age mounds etc etc) and subject them to enough analyses seemingly meaningful patterns will be found. However, the trick is proving whether these apparent patterns are a function of meaningful action by a past society or just a freak of statistics. Another example of this is the work by Charles Thomas drawing on the approach developed by David Howlett on Biblical Latin Style on the early medieval inscriptions of Wales and Western Britain. Thomas’s analyses of these inscriptions seem to show messages (and even images) hidden within these simple inscriptions (this is best laid out in his his book Celts: Messages and Images. Stroud: Tempus, 1998). He argues that these messages can be made visible by certain mechanisms such as letter counting and the ascription of numeric values to letters. However, his critics point out that it is possible to identify hidden messages using such techniques in almost any text if you analyse it in enough different ways – is it a case of the ‘wisdom of ancients’ or simply infinite monkeys producing, if not Shakespeare, then at least Biblical Latin?

Imagined Village

Very excited about the new Imagined Village album- the first album was one of my picks of 2007. Of course, although there is a tour, they are not playing anywhere I can get to…

Very excited about the new Imagined Village album- the first album was one of my picks of 2007. Of course, although there is a tour, they are not playing anywhere I can get to…

Setumaa

Whilst searching something for entirely different I’ve just come across this old picture report from the BBC news website about the Seto people who live in the south-east border of Estonia and the neighbouring area of Russia . We went to Estonia in 2004 and spent some time in Setumaa (the land of the Setos) whilst we stayed nearby. The Seto are an Orthodox minority within Estonia where the main religion is technically Lutheran. They still maintain their traditional culture very strongly, particularly their folk song and their polyphonic choral tradition has recently been inscribed on the UNESCO list of intangible cultural heritage.

Whilst searching something for entirely different I’ve just come across this old picture report from the BBC news website about the Seto people who live in the south-east border of Estonia and the neighbouring area of Russia . We went to Estonia in 2004 and spent some time in Setumaa (the land of the Setos) whilst we stayed nearby. The Seto are an Orthodox minority within Estonia where the main religion is technically Lutheran. They still maintain their traditional culture very strongly, particularly their folk song and their polyphonic choral tradition has recently been inscribed on the UNESCO list of intangible cultural heritage.

It was when we were exploring this forgotten corner at the edge of Europe that I really fell for Estonia and its history- this has led to the accumulation of far too many books on Estonian archaeology. I’m desperate to some fieldwork there at some point…

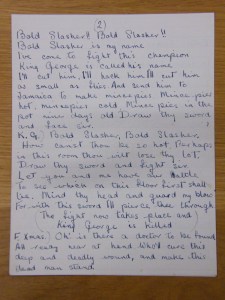

Mumming Plays

It’s the time of year for mumming plays. I got to see one performed in Wantage on Boxing Day this year- the text of the play is actually recorded from my parent’s village of Steventon (which is just down the road). Fortuitously, whilst I was working on archives at the Museum of English Rural Life research H.J.Massingham I came across the text of a mumming play which I think has not previously been published – it was in a box along with the manuscript for an projected book written by Massingham on Cotswold folk-tales and humour. It is very similar to one from Snowshill (Gloucestershire) so I presume its from somewhere in the neighbourhood. The copy of the text is not written in Massingham’s hand, so I presume it was passed to him by someone else; presumably at some point in the 1930s.

It’s the time of year for mumming plays. I got to see one performed in Wantage on Boxing Day this year- the text of the play is actually recorded from my parent’s village of Steventon (which is just down the road). Fortuitously, whilst I was working on archives at the Museum of English Rural Life research H.J.Massingham I came across the text of a mumming play which I think has not previously been published – it was in a box along with the manuscript for an projected book written by Massingham on Cotswold folk-tales and humour. It is very similar to one from Snowshill (Gloucestershire) so I presume its from somewhere in the neighbourhood. The copy of the text is not written in Massingham’s hand, so I presume it was passed to him by someone else; presumably at some point in the 1930s.

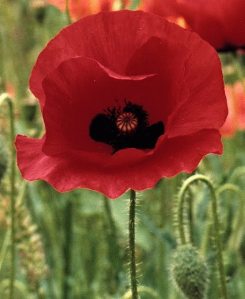

Armistice Day

Today is the first time Armistice Day has been remembered without any World War I veterans attending the ceremony at the Cenotaph. The last two British veterans of the war, Harry Patch and Henry Allingham, died earlier this year.

Today is the first time Armistice Day has been remembered without any World War I veterans attending the ceremony at the Cenotaph. The last two British veterans of the war, Harry Patch and Henry Allingham, died earlier this year.

As a child I remember watching the Remembrance Parade on television, and enjoying the march past of the former soldiers from both World Wars; the lack of WWI veterans this year is a stark reminder of how both of these momentous events are slipping away from living memory. Even the numbers of World War II combatants is increasingly tiny and physically frail.

For anyone growing up in England over the last thirty years, both wars will loom large in their cultural memory. Many people study the war poets at school: Wilfrid Owen, Siegfried Sassoon, Robert Graves and others. There were also the direct personal links with those who’d lived through them and experienced loss. My grandmother lost four male relatives, including her father in World War I. My great-grandfather got a medal for shooting down the first Zeppelin over London (even though he was stuck on a train at the time). One of my grandfathers served in India, whilst the other repaired tanks in Egypt: my great uncle came in on the beaches at D-Day. I have a photograph of a family wedding from during the war; it was a large family and every single male was in military uniform. It’s difficult from our modern perspective, when the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq seem impossibly remote to imagine the extent to which these wars permeated all aspects of life and how they impacted on life and society after the war; my great grandmother struggled to bring up two children single-handed in London in the 1920s. Even though all these things are slipping away from immediate personal experience and memory, its worth pausing for a moment or two to remember them

Family Roll of Honour

Private James Patrick McManus DCM, 2nd Bn, Kings Own Scottish Borderers, 6th May 1915

Private Patrick Canavan, 1st Bn, Royal Irish Fusiliers, 10th May 1915

Private Albert Hollowell, 24th Bn, London Regiment, 28th October 1915

Sapper William Hollowell, Inland Water Transport, Royal Engineers, 24th January 1919

Archaeology and the BNP

Interesting piece of comment arising out of last week’s Question Time in today’s Guardian

Interesting piece of comment arising out of last week’s Question Time in today’s Guardian

Having been poking around some of the seemier (politically) ends of the internet over the weekend, it’s interesting to see what use the BNP/Far Right is using of archaeology. Particularly, they appear to have picked up on the work of Stephen Oppenheimer who has used genetics to suggest that the British population has its origins with pre-Celtic populations and was not profoundly influenced by later migrations. (NB: that is a very broad characterisation of his more subtle argument; its also important to note the Oppenheimer has publically disavowed the racist/political spin put on his work by the BNP. It is of course possible to make a critique of Oppenheimer on technical grounds (though I’m not particularly well-placed to do this); however whether accurate or not I am interested in the way in which his work is being used.

Essentially, the BNP are arguing that this means we can clearly distinguish an ‘indigenous’ British (which they often gloss as ‘English’) population which they see as countering the argument put forward by many of those who are anti-BNP that Britain has always been a melting pot, with great genetic diversity (thanks to ‘Celtic’, Roman, Anglo-Saxon, Viking, Norman etc interbreeding).

The problem with the BNP use of Oppenheimer’s work is that they elide the notion of race as defined by genetics/descent and the notion of a people/ethnic group, as defined by cultural practices. So, if we accept that Oppenheimer is right, then the BNP have the problem that although there is a broadly genetically homogenous indigenous population in the UK, its cultural practices have continually been reworked by incoming cultural groups. Whatever the current debates about the size of Anglo-Saxon migrations, it is pretty clear that the 5th-8th centuries saw a profound ‘germanicisation’ of much of lowland England. The far right then have to accept the fact that Anglo-Saxon society (in its archaeological sense and in its modern politicised sense) is something that has been imposed on an indigenous population. Thus, it makes it hard for them to criticise on an a priori basis the notion that externally derived cultural change is a ‘bad thing’. On the other hand, if they reject Oppenheimer’s work (or it becomes discredited), they have to accept that actually, our ‘pure’/’indigenous’ population is nothing of the sort.

However, I suspect that detailed exegesis of the current work on population genetics and archaeological culture theory is not at the top of their minds. However, this is an excellent example of how archaeology (in its broadest sense) is being used to fuel pressing current political debates.

More on Norman churches…

The first blast of the beginning of term is now over, so I’ve finally found time to have a bit of a think about the results of my initial fieldwork in Western Normandy which I’ve blogged about previously.

The first blast of the beginning of term is now over, so I’ve finally found time to have a bit of a think about the results of my initial fieldwork in Western Normandy which I’ve blogged about previously.

Essentially, I’m interested in exploring the development of early Christianity in the Cotentin peninsula in West Normandy; this is a border region between Normandy and Brittany. The received wisdom (primarily based on fairly limited documentary evidence) suggests that in the pre-Viking period (ie pre-10th century) there were only a small number of ecclesiastical sites in the region incuding Portbail, Orval, Coutances, St Marcouf and Le Ham (near Valognes). These are assumed to have fallen into abeyance following Viking raiding, with church organisation only reviving in the 11th century. Although little has been written about the rise of the parochial system there is a general assumption that this only falls into place in the 11th/12th century, although this has never really been tested.

My current working hypothesis is that there are two problems with this existing story. First, I am suspicious of the fact that in the pre-Viking period there were only around six ecclesiastical centres. For example, in England, County Durham (an area of comparable size) has around fifteen known pre-9th century monastic/church sites. I believe that there is enough reported archaeological evidence (primarily in the form of Merovingian burials) from later church sites to argue that they had pre-Viking origins. Of course, I am making some key assumptions here, particularly that this reported evidence is indeed of pre-Viking date. One of my key tasks now is to go back to the original (mainly antiquarian) publication of the evidence for early activity on later church sites to assess its reliability – luckily thanks to the Society for Church Archaeology I have a small grant which will allow be to visit the British Library and the Bodleian Library to consult the relevant publications.

My second suspicion about the current narrative is that there was a large-scale disruption of Christianity in the region following Viking settlement. I have no problem with some sites being raided and temporarily falling out of use, but I’m not convinced there was a complete abandonment of the churches until the 11th century. Again, based on the presence of pre-Viking activity on later church sites I would argue that there is continuity straight through. Otherwise we’d have to argue that the memory of the location of church sites was preserved for at least a century and then when Christianity was re-established the churches were revived on the original locations rather than new sites.

I am also interested in the spread of parishes. I am happier that the 11th/12th century date posited is correct. However, I think there is a still a need to provide more hard evidence. One way of exploring this is through looking at the provision of churches in this period. This can be done using the limited documentary evidence and the architectural evidence. The charters issues by the Dukes of Normandy are of some help; a number of churches are mentioned in the grants they made, particularly to abbeys, in the 10th and 11th centuries; although it is noticeable that there are geographical variations in the evidence for these churches. For example, quite a few are recorded in the central Cotentin (Barneville-Carteret; Valognes; Briquebec areas), but far fewer in the north. How does this correspond with the evidence from the churches themselves. Well, again, there is a traditional narrative here. Most overviews of early Romanesque architecture in the region (broadly speaking 11th-12th century AD) limits themselves to a fairly limited number of sites; primarily those which contain large quantities of Romanesque sculpture or extensive areas of fabric (for example, Tollevast, Martinvast; Octeville; Brucheville). However, my gut feeling, based on previous visits to the area, was that, in fact, there were many more churches than that which preserved at least some early Romanesque fabric (based on the presence of various diagnostic features, such as the use of herring-bone masonry and monolithic stone windowheads. Thanks to a grant from the Society of Medieval Archaeology I was able to spend some time out in the region in September doing a rapid but systematic survey of churches in a number of sample areas across the Cotentin. I looked at around 140 churches and recognised a far higher level of existing fabric of this period than had previously been suspected (you can see lots of images here. It was interesting to note how poor the local understanding of church architecture could be; for example, at la Haye D’Ectot. , the information board firmly stated that the building was built in the 18th century, despite the clear presence of 12th century fabric in it! .

Although there is still much of the area to survey, it is clear that the documentary evidence significantly under-represents the provision of churches in the area in the 11th/12th century. There are a number of areas, such as that around the Sienne estuary, where there are entire blocks of parishes which have churches with 11th/12th century fabric, suggesting that the parish network was established by this point.

So, still lots of work to do pulling together all the documentary and antiquarian evidence together. I’d also like to explore the landscape context of the churches in a little more detail at some point: many of them are in hilltop locations and in some areas they are often located well away from the modern villages.