After the death of Oliver Postgate just before Christmas, its sad to see that Tony Hart has died. Its rather disconcerting to see the landmarks of one’s childhood starting to die off.

Clogging it

After the previous post and my reference to clog dancing, I was watching Folk America at the Barbican: Hollerers, Stompers and Old-Time Ramblers, which features a bit of Appalachian clog dancing (about 8 minutes in), a reminder that this British tradition went to the States early (pre-1800) and became a key element in the Appalachian and Ozarks musical tradition.

Morris dancers: a protected species.

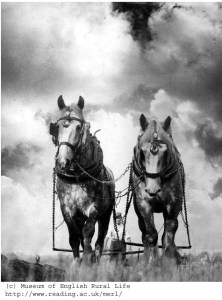

Back to the blog after the festive season (and two weeks nose to the grindstone working on the book). Anyway, something popped up in the news in the New Year which caught my eye/ear/eyes (delete as applicable). Apparently, morris dancing is under threat. This is something that seems to come up fairly regularly (and it would help the case a little if The Morris Ring who were behind this piece of publicity allowed women to dance!). However, morris still appears to be in fairly rude health, both in terms of numbers and dare I say it artistically. Few would deny that the morris tradition was heavily resuscitated by the folk song movement in the early 20th century (Cecil Sharpe and others of that ilk), but it is a genuine living tradition, and there are dance sides, such as Bampton and Headington (see picture above) which have an unbroken history back into the mid 19th century and probably earlier. The numbers of dancers is at a good level, and crucially young (and I mean younger than me) dancers are still taking it up. Sides like the more arty/performance based Morris Offspring and the more traditional but still ballsy Dogrose Morris show that morris needn’t mean accountants flouncing with hankies (you can see Dogrose Morris on Jools Holland later here).

Its also important to remember there is a lot more to English traditional dance than the traditional morris dancing (the Cotswold/Oxfordshire tradition); there is also border morris found along the Welsh borders, which has its own distinct dances and costumes (including painted faces) and rapper/sword dancing from Yorkshire and the North East – the latter with a traditional costume based on the work clothes of 19th century miners. Not all traditional dancing was based round team dances; there is also a tradition of solo clog dancing (I think this is mentioned in Ronald Blyth’s wonderful book Aikenfield)

Christmas Champions

Once again, I’ve missed the opportunity of going to see a performance of English Acoustic’s Collective exploration of the British mumming tradition Christmas Champions, though its still possible to catch the original broadcast for Late Junction on which it was based. There is also an interesting article from Folk World about its genesis.

Once again, I’ve missed the opportunity of going to see a performance of English Acoustic’s Collective exploration of the British mumming tradition Christmas Champions, though its still possible to catch the original broadcast for Late Junction on which it was based. There is also an interesting article from Folk World about its genesis.

Sadly, this year I won’t be able to catch the Mummer’s Play in Wantage on Boxing Day, which has become a bit of a family tradition in recent years. Its not such a tradition up North, where the plough stotts are more common. I’d like to think I’ll catch the Goathland plough stots, but suspect we won’t make it… (I am now wishing I’d brought the original 1913 pamphlet on the sword dances of Northern England by Cecil Sharp, which I saw in Fossgate Books today..doh!)

Collecting England

Jane recently came across the website for the brilliant Pitt Rivers Museum Inside England project. It won’t come as a surprise given my recent posts how interesting I’ve found this. Partly for the highly entertaining object biographies (Tylor’s bewitched onion anyone?) and partly because its got me thinking about the history of collecting English folk/vernacular objects. As the name of the museum suggests, it was founded by General Augustus Pitt-Rivers, one of the founding fathers of British archaeology. His influence was greatest in the development of field techniques, but he was also important as one of the earliest field archaeologists to beging to place his practical archaeology in a broader theoretical framework. Not surprisingly for someone of his dates he seized upon Darwinism and evolutionary approaches. He was also dedicated to promoting and popularising archaeology and education more generally. He opened his private estate as a kind of educational pleasure ground and also built up collections of a wide range of objects and artefacts, often arranged typologically to illustrate the process of evolution through the change in form of objects. His early collections certainly included contemporary (ie 19th century) objects, and much of his early thoughts about material culture and evolution were worked through in his collection of firearms.

Jane recently came across the website for the brilliant Pitt Rivers Museum Inside England project. It won’t come as a surprise given my recent posts how interesting I’ve found this. Partly for the highly entertaining object biographies (Tylor’s bewitched onion anyone?) and partly because its got me thinking about the history of collecting English folk/vernacular objects. As the name of the museum suggests, it was founded by General Augustus Pitt-Rivers, one of the founding fathers of British archaeology. His influence was greatest in the development of field techniques, but he was also important as one of the earliest field archaeologists to beging to place his practical archaeology in a broader theoretical framework. Not surprisingly for someone of his dates he seized upon Darwinism and evolutionary approaches. He was also dedicated to promoting and popularising archaeology and education more generally. He opened his private estate as a kind of educational pleasure ground and also built up collections of a wide range of objects and artefacts, often arranged typologically to illustrate the process of evolution through the change in form of objects. His early collections certainly included contemporary (ie 19th century) objects, and much of his early thoughts about material culture and evolution were worked through in his collection of firearms.

However, his collections of English material appear to have primarily use to illustrate and develop his theories and not particularly because he saw the wider value of treating England as a subject of ethnographic study, comparable to the fields of enquiry being developed abroad (particularly within a British imperial context) by British anthropologists.

I’ve not been particularly succesful in finding out more about the growth of the collecting British material in a broadly ethnographic context. I’d presumed that it must have had its roots in the early 20th century ‘folk’ revival, though I’ve not come across any details. I suspect that the early collections were largely put together by private individuals and did not reach museum collections for some time. For example, Hugh Massingham had a collection of various rural tools and equipment, which he put together in the between the 1920s and early 1950s when he died. However, the museum which they are now in The Museum of English Rural Life was not founded until the year he died. Beamish, the museum near Chester-le-Street dedicated to the local way of life was not founded until 1970, the same year as the Weald and Downland Museum. Many other major private collections of this kind of material is still finding its way into museums (such as the Harrison Collection) which has just been acquired by the Ryedale Folk Museum. I am sure there are also many small collections of ‘social life’ material in minor local museums, which are not presented or extensively promoted. Noticeably it was not until the post-war period that entire museum’s were dedicated to this kind of material. There is still no national museum dedicated to English folk life and culture, unlike Wales, where the St Fagan’s National History Museum is part of the National Museum of Wales. From my limited knowledge, this makes England relatively late to start taking the collection of indigenous objects seriously; for example in Sweden, the celebrated open air museum at Skansen was founded in 1891.

English Folk Culture (and a bit about Napoleon)

After my recent post on defining Englishness I’ve just come across the work of Sarah Barber who is developing research on defining English Folk Culture addressing some of the methodological issues in defining what we mean by ‘folk culture’. I am not sure I entirely agree with some of the working definitions she is using, but its useful to see someone attempting to define ‘folk’ as cultural category of analysis(as opposed to what has now become an aesthetic genre). I think her attempt to define ‘folk’ as a relationship between the individual and the collective is a useful approach and avoids sterile arguements about what is inside or outside the folk tradition.

Its important to distinguish the search for a working definition of ‘folk’ as different from a working definition of Englishness (if such a slippery subject can be defined). There is no direct or easy equation of English folk culture with ‘Englishness’, which is often defined using exampla drawn from a range of sources from Imperial History, the Anglican church (bells and smells or happy clappy) and other criteria derived from middle class culture. Indeed the search for Englishness might be defined as a particuarly middle class neurosis. Folk culture, however, makes an overt reference to national identity and in many cases, particularly in the musical tradition, drawns on radical and republican discourses that are inherently anti-Nationalistic. For example, there is a fascinating tension in the depiction of Napoleon and the French Revolution in English folk song; compare the words of The Liberty Tree

It was the year of ’93

The French did plant an olive tree

The symbol of great liberty

And the people danced around it

O was not I telling you

The French declared courageously

That Equality, Freedom and Fraternity

Would be the cry of every nation

with

Come listen every lord and lady, squire, knight and stateman,

I’ve got to sing a little song about a very great man;

And if the name of Bonapart should mingle in my story,

It’s with all due submission to his honour’s worship glory.

He fell in love with Egypt once because it was the high road

To India for himself and friend to travel by a nigh road,

And after making mighty fuss and fighting night and day there,

‘Twas monstrous ungenteel of us who wouldn’t let him stay there

Though to be fair, I wonder how many of the pro-Boney songs are from the Irish rather than English tradition. Its also worth mentioning my favourite lyric

My uncle, Captain Flanigan,

Who lost a leg in Spain,

Tells stories of a little man

Who died at St. Helene;

But bless my heart, they can’t be true,

I’m sure they’re all romance;

John Bull was beat at Waterloo!

They’ll swear to that in France

ANYWAY….coming back to Sarah Barber’s work, on far more trivial matter, I was pleased to see that one of her interviewees was on Joseph Porter drummer, lead singer and song writer of one of the words greatest bands, Blyth Power (named after a Class 56 diesel don’t you know), possibly the only band to have ever written song about Graf von Tilley, the 30 Year War and the Battle of Breitenfeld!

In the lands of the North, where the Black Rocks stand guard against the cold sea…

I’ve just heard the sad news of the death of Oliver Postgate, creator of Bagpuss, The Clangers, Ivor the Engine and Noggin the Nog. These programmes defined my early childhood, and that of almost anyone else who grew up in the 1970s. I’ve recently started seeing some of the modern children’s programmes, and without wanting to come over all nostalgic, they don’t hold a candle to this classic era of British television (though I do have a soft spot for In the Night Garden). Listening to excerpts from Postgate’s programmes on the radio this mornign, what really struck home was their immense seriousness. They could be light hearted in places, but it was in their solemn attention to simple matters they were at their most childlike (in all the good senses of the word).

Tam Lyn

With reference to the previous post- I’ve just found this on You Tube. Its from the Imagined Village; a version of the traditional folk ballad Tam Lyn by Benjamin Zephania. There is also a version of Cold Haily Windy Night from the same album. For those who are interested in these thing, the driving force behind the album is Simon Emerson, who is also the main man of Afro-Celt Sound System. Imagined Village also involved Paul Weller, Billy Bragg, Eliza Carthy, the Dhol Foundation amongst others.

Idea of Landscape

I’ve finally had time to put down my thoughts about Matthew Johnson’s Ideas of Landscape , which I’ve recently re-read. In this book Johnson explores the distinctive English tradition of (primarily medieval) landscape archaeology, which has its roots, or at least is personified in the form of W G Hoskins, author of the Making of the English Landscape. He situates Hoskins as the inheritor of a wider Romantic tradition of writing about landscape; one which he sees as both empiricist and conservative. He argues that the methodology of much landscape archaeology in this mould is undertheorised, particularly in the way in which it goes through the process of interpretation. In Johnson’s eyes, for the English landscape tradition the process of understanding field archaeology is unproblematic and essentially a procedure which involves the reconstruction of landscapes using models derived from historic sources. He focuses on what he sees as the empricist inferences behind the ‘mud on the boots’ emphasis on fieldwork and the tyranny of the Cartesian gaze in the use of maps and aerial photographs.

One of my major problems with this book is that Johnson misses the chance to turn his critique on many of the post-processual approaches to landscape. I would argue it is also possible to see the influences of the (Neo-)Romantic landscape tradition running through the phenomenological tradition (e.g. Chris Tilley) and what Andrew Fleming has called the hyper-interpretive approaches (for example in the work of Mark Edmonds). These are characterized by fixing on the experience of landscape (both in the past and by the modern investigator) and an aestheticised gaze. They are as reliant on ‘gut reaction’ as part of the interpretive process as is the English landscape tradition. Andrew Fleming has explored the methodological limitations of these approaches in a couple of recent papers (Camb Arch Journal 16/3 2006; Landscapes 8/1 2007). Because Ideas of Landscape focuses on the medieval landscape tradition, rather than approaches to prehistoric archaeology, which is the main arena for much of these post-processual approaches to landscapes, he misses exploring the more complex relationship between Romanticism and archaeology. In his eagerness to place the blame for all the problems (and there are undoubtedly many problems) with landscape archaeology in England on the Romantic tradition, he fails to see the complexity of this important tradition in British thought and its pervasive influence on archaeology in the UK. He briefly acknowledges the important stream of political radicalism in the Romantic tradition (such as Blake, Crabbe and Orwell)but fails to develop this line. By drawing all his fire on the Romantic geneaology of Hoskins et al, he fails to explore the way in which the empiricist approach to archaeology derives much from the Enlightenment project, which much Romantic thought deliberately set itself against.

As is also common in archaeological critiques which explore the intellectual genealogy and context of other scholars and traditions, the book fails to contextualise itself adequately. I would have liked to see Johnson carry out an element of auto-critique to his own work. Although he mentions his experiences as a student at Wharram Percy, he fails to situate his own work in a cultural tradition. There are hints of his preferences; he prefers the ‘naughtiness, travelling, whoring and sharp comment on the social iniquities’ of the 18th century to the sentimentality of Romanticism. But it is hard to get a sense of his own personal academic journey, which is a pity, as his own output on post-medieval archaeology shows some interesting biases. For example, he manages to write a book on the Archaeology of Capitalism which hardly mentions industry or industrial archaeology. Is this deliberate? Is there a methodological or theoretical reason for this, or even (whisper it quietly) a degree of anti-modernism in his own scholarship…

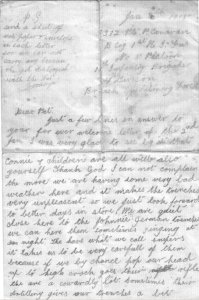

World War I Letter

This letter was written by my Great-grandfather’s cousin, Private Patrick Canavan (Royal Irish Fusiliers), from the trenches in WWI. It is dated January 1915; he was killed in the Second Battle of Ypres four months later; he was just twenty-eight years old. He lived on Kashmir Road, Belfast, and left a wife, Rose, behind him. He is buried in St Sever Cemetery in Rouen.

My great great uncle, James Patrick McManus (Kings Own Scottish Borderers), was killed in the same battle four days earlier. His body was never found, but he is remembered on the Menin Gate at Ypres. He had previously won the Distinguished Service Medal.