This is the text of a paper I gave at the MR James conference (M R James and Modern Ghost Story) in Leeds earlier this year- it’s unedited, unreferenced (and pretty much unproofread), but hopefully will be of interest to some- if you are interested in a copy of the accompanying Powerpoint just drop me a line:

The material past looms large in the ghost stories of M. R. James. In almost all his stories, the supernatural crisis is catalysed or channelled through a physical object, sometimes a manuscript or book (The Tractate Middoth), sometimes an image (The Mezzotint) and sometimes physical objects, as diverse as a bone whistle, a dolls house or a strip of wallpaper. Although James’ academic work was primarily focused on the study of text, both as editions and as physical manuscripts, it also engaged widely with physical objects, particularly sculpture, stained glass and wall paintings – what Monty himself described as ‘Christian archaeology’. As well as this interest in the materialised past, practitioners of the study of the past, archaeologists and antiquarians, also make regular occurrences in his stories, some simply as supporting cast (the FSA in An Episode of Cathedral History; the archaeologist in ‘O Whistle and I’ll Come to you my lad’or the doomed barrow digger, Paxton in ‘A Warning to the Curious’. In this paper, I want to draw out and cotnextualise MR James engagement with archaeology. Exploring his own direct and indirect engagements with the emerging discipline in the later 19th and early 20thcentury and also highlighting the ways in which he harnessed his engagement with archaeology in his ghost stories.

Tracing its origins back to scholars of the 16th and 17thcentury, such as William Camden (1551-1623) and John Leland (1503-1552), the early study of the physical remains of the past had been dominated by an antiquarian perspective. Early writers, drew on the chorographic tradition, structuring studies by region or area – taking a broad approach, recording genealogical information, information about important buildings, snippets of folklore, natural wonders and unusual objects, this encyclopaedic approach revelled in juxtaposition and collation, but made little attempt at either chronological or regional synthesis. Often drawing on local informants, early antiquarians carried out little fieldwork beyond the occasional illustration of significant castles or abbeys. However, these were the first sustained engagements with the recording of antiquities- and crucially marked the beginning of the rediscovery of the middle ages, treating pre-Reformation texts and monuments as both worthy of study but also bracketing them off as belonging to antiquity allowing a narrative of rescue and rediscovery to be sustained. A prime example of this can be seen in the work of the antiquary John Aubrey- like many early antiquaries he was a polymath – best known outside archaeology for his biographical sketches ‘Brief Lives’ he published widely on folklore, place-names, antiquities and with his Monumenta Britannica he was a key figure in trying to understand major prehistoric monumental complexes, such as Avebury and Stonehenge. However, whilst this prehistoric material dominate the modern perception of his archaeological interests, he was also a key figure in developing approaches to the medieval past- his unpublished, yet influential, Chronologia Architectonica of 1670 was an attempt to develop a chronological typology of medieval architecture and crucially contained not just physical descriptions but illustrations drawn by Aubrey himself in the same way he surveyed in his plans of prehistoric sites.

The long 18th century saw the development of the antiquarianism, both in terms of scope and methodology but also its institutional structure. First, the level of recording and fieldwork developed- building on the methods of Aubrey and others. Excavation whilst often exceptionally crude by modern standard was increasingly carried out- classically on prehistoric burial mounds. Major early excavators included figures such as the Reverend Bryan Fausett (1720-1776) and the Reverend James Douglas (1753-1819) – the former opened over 700 barrows, prehistoric and Anglo-Saxon over his career. The 18th century thus saw an increasing emergence of prehistory as a distinct sub-field, comprising both standing monuments and excavated remains. However, whilst figures such as William Stukely – more commonly associated, like Aubrey, with work on prehistoric sites, did record medieval buildings, medieval archaeology was treated as a topic for which the main resource were standing buildings rather than a field for subsurface intervention. The motif of barrow breaking was however used by James in A Warning to the Curious although in this case in the context of an Anglo-Saxon rather than a prehistoric barrow.

A major development for the wider field of antiquarianism was the establishment of the Society of Antiquaries of London in 1707 and receiving its royal charter in 1751. This provided an institutional focus for antiquarian pursuit in England- as well as crucially being responsible for a series of journal – most notably Archaeologiaand Vetusta Monumenta – both of which published from the very beginning material on medieval topics.

Rather topically, one of the few areas where medieval antiquities were actively investigated through excavation was the graves of kings. Particularly under the stimulus of Richard Gough, Diretor of the Society of Antiquaries from 1771 to 1797. In 1774, the tomb of Edward I was opened in Westminster Abbey revealing both the body and associated grave goods, Edward IVs grave in St George’s Chapel, Windsor, was opened in 1789, and King Johns grave excavated in Worcester Cathedral in 1797. This investigation of graves clearly finds resonances in some of James’ stories, particularly An Episode of Cathedral History- but as we shall see he also later had a more direct involvement in the opening of medieval graves.

The later Victorian saw changes in emergence of deep time- scientific understanding of prehistory particularly due to increase of excavation – drawing on notions of social evolution ultimately derived from Darwinism, but also principles of stratigraphy derived from geology, all of which profoundly influenced the development of archaeology as discipline. But the mid 19th century also saw the establishment of an increasingly structure academic framework for the archaeological study of the past. Crucially this was the great period of the flowering of national, county and local archaeological societies. A key moment was the establishment of the British Archaeological Association in 1843, in reaction to a perceived over emphasis on earlier periods of history by the SA, as well as a perception that it was London-biased and aristocratic. The aims of the BAA were clearly “for the encouragement and prosecution of researches into the arts and monuments of the early and middle ages” . Amongst its aims were the organisation of an annual archaeological congress, along the model of the French Congrès Archéologique or the annual meetings of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. There was a rapid schism however, partly along class lines. The majority of the founders of the BAA were from trade backgrounds, but following a squabble about publication, a new Archaeological Institute was founded by a faction led by Albert Way of a notably differing class complexion. Despite the increased ‘professionalization’ of the archaeology and antiquarian studies in this period, the remit of both societies was still very wide. The first volume of the Archaeological Journal published by the Archaeological Institute including papers on Roman London, Observations on the Primeval Antiquities of the Channel Islands, On Anglo-Saxon Architecture and, and I quote ‘The Horn-shaped Ladies’ Head-Dress in the reign of Edward I “. The term ‘archaeology’ still had a wide semantic range and in the words of Chris Gerrard “the relationship between antiquarianism, historians, architects and archaeologists was uncertain territory”.

The mid-19th century saw a huge range of other societies being established at this time – both historical- the Surtees Society 1834, the Early English Text Society 1864, the Harleian Society 1869, and archaeological –By 1886 there were some 49 county and local archaeological societies, including the Cambridge Antiquarian Society of which James became a member. It is to this kind of society that Baxter, the antiquary, in A View from a Hillseems to have belonged. The protagonist “spend a morning half lazy, half instructive in looking over the volume’s of the County Archaeological Society’s transactions in which were many contributions from Mr Baxter on finds of flint implements, Roman sites, ruins of monastic establishments – in fact most Departments of archaeology.”. In the story, Baxter was the local watch maker, and this reflects an important aspect of the widening of archaeology as a sphere of research, a process of social democratization. Even as early as the early 19th century, not all antiquarians were of aristocratic, gentry or ecclesiastical backgrounds. William Cunnington, the important early 19th century field worker was a local merchant.

A facet of many of these early societies was an increasing emphasis on campaigning to preserve and protect historic monuments- something which was not within the constitution or ambition of the Antiquaries. Despite the rampant medievalism of mid-Victorian society, with the emergence of Gothic as a natural architectural style with figures such as Pugin and Gilbert Scott in the vanguard of this taste-making, historic monuments were increasingly under threat. Indeed, it is this very resurgence of medievalism that led to a sustained attack on the historic fabric of Britain’s churches. The Oxford movement with its aim to revive and renew traditional and more Catholic styles of worship led to an assault on the interiors of medieval churches with later features regularly removed and stripped back to achieve an allegedly more authentic, medieval style. This movement was motivated by an enthusiasm for the medieval – the aims of the Cambridge Camden Society, so closely associated with this thrust, were “to promote the study of Ecclesiastical Architecture and Antiquities and the restoration of mutilated Architectural Remains”. However, the followers of the Camden society and its Oxford counterpart, the Oxford Society for Promoting the Study of Gothic Architecture did great harm to the historic interiors of British parish churches. Despite both his loyalties to the Victorian world (remember if you please that I am a Victorian by birth and education…”)and his love of the medieval, James’s attitude to this medievalism was one of ambivalence. His preferred architectural style appears to have been neo-Classical, and the unconstrained and insensitive removal and reordering of the 17th and 18th century interiors of medieval cathedrals to be replaced by neo-Gothic furnishings is at the core of An Episode of Cathedral History, and the fragment of medieval stall and its associated paper message presumably came to the knowledge of the narrator following their removal from the cathedral. It was in reaction to such destruction thatWilliam Morris founded the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings in 1877, although the views of the ‘anti-scrape’ as it became known were not always popular.

A wider concern about the destruction of historic and archaeological monuments reached parliament and steered by Sir John Lubbock, 1st Baron Avebury, in 1882, the Ancient Monuments Protection Act was passed. Lubbock was an important figure in the development of prehistoric archaeology in Britain – heavily influenced by social Darwinism, he was writer of some of the first major syntheses of the development of prehistoric society, coining the terms Palaeolithic and Mesolithic. If the name Lubbock rings a bell for many of you, it most likely because one of the early memoirs of M R James was written by Samuel Gurney Lubbock – a nephew of John Lubbock. Monty was also friends with John Lubbocks sons, Harold and Eric. He certainly visited the Lubbock family home, where he met Baron Avebury’s second wife, Alice Pitt-Rivers, daughter of Augustus Lane-Fox Pitt-Rivers, another towering figure in late Victorian archaeology.

But how does MR James relate to this wider development of archaeological endeavour in the later 19th and early 20th century?

As a child he wrote to his father that he wanted “above all things to make an Archaeological search into the antiquities of Suffolk, to get everything I can for my museum” and later that he planned to “prosecute my archaeological studies at the Guild-Hall library in the holidays”. Growing up in rural Suffolk he lived in an area with a strong antiquarian tradition – indeed, the sons of one of the earlier vicar’s of Great Livermere “Honest” Tom Martin was a noted Suffolk antiquarian and the Suffolk Institute for Archaeology was founded in 1848. One possibility I have not been able to confirm is that James knew about the excavation of the important Anglo-Saxon boat burial at Snape – probably of a member of the East Anglian royal family these burials and the associated barrows stood on the main road into Aldeburgh, where he spent much time as a child. The tumulus was obvious and is shown clearly surviving on the 1stEdition Ordnance Survey map. It seems inconceivable that given his proclivities he was not aware of it and must have consciously or unconsciously fed into the plot of a Warning to the Curious, particularly given its setting in Seaburgh, clearly based on Aldeburgh.

Despite his occasional roof-climbing adventures, Monty had relatively little exposure to archaeology or ecclesiology at Eton. However, when he arrived at Cambridge he emerged into a city and university on the leading edge of the disciplinary development of archaeology. We might perhaps at this stage identify three key, distinct, but cross-fertilising streams in archaeology. Prehistoric archaeology, being pushed forward by Lubbock and others, medieval archaeology, which was still a blend of more scientific approaches but still heavily influenced by antiquarian and art historical perspectives, and finally, an area I’ve not yet touched on, classical archaeology. This latter field grew out of the world of classical studies and was profoundly text led and art historical, but with a commitment to excavation. Classical archaeology was in particular going through a phase of rapid development – in the decade leading up to his arrival at King’s in 1882, in particular the work of Schliemann at Troy had received international acclaim.

Cambridge University was the first British university to have an endowed chair in Archaeology- the Disney professorship set up in 1851; it required the holder to give three lectures a year for a stipend of £100. In O Whistle.. the ‘person of an antiquarian persuasion’ who encouraged Parkins to visit the site of the Templar preceptory was given, in a typical MR James in-joke, the name Disney. On his arrival at Cambridge, the holder was Percy Gardner, a specialist on Greek art , with close connections to the British Museum, but someone whose engagement in research was from the perspective of connoisseurship rather than fieldwork.

It is important to remember that MR James arrived at Cambridge to study the Classics tripos and he selected Classical Archaeology for special study in Part II of the Tripos: he wrote in 1885 ‘the field is so frightfully wide that I want all the time I can get, and not sanguine about the results. Sculpture, painting, coins, inscriptions, mythology, gems –each of these implies a good deal of reading”. Much of his learning was closely supervised by Charles Waldstein, American archaeologist and Olympic shooter who at the time was Director of the Fitzwilliam Museum,. Monty was soon appointed Assistant Director eventually succeeding to the Directorship after Waldstein, although in this position he focused primarily on the acquisition of manuscripts rather than artefacts.

It was in the domain of classical archaeology that he made his first, and most significant, engagement in field archaeology. In 1887, Henry Babington-Smith an Eton and King’s College contemporary of Monty’s was granted £150 to engage in archaeological fieldwork in Cyprus – under the auspices of the Cyprus Exploration Fund, set up with support of the Hellenic Society. However, he instead took up a civil service job as an examiner in the education department. Monty was asked to accompany the expedition at short notice. The overall project was led by Ernest Gardner, the younger brother of Percy Gardner (Disney Professor) – who was the Director of the British School at Athens- who had excavated with Flinders Petrie. Another participant was David Hogarth, who ended up as Director of the Ashmolean Museum, and was later a close friend of T E Lawrence, for whom he was first an academic influence in Oxford and then served alongside in the Arab Bureau during WWI. Whilst Gardner was an experienced excavator, Hogarth recalled in his memoirs that the others ‘were so raw as not to know if there were any science of the spade at all’. The focus of the excavations was the Temple of Aphrodite, but also included exploring a number of other related sites. James had two roles, on site he seems to have led with the study of the epigraphy, transcribing and translating the many inscriptions found during the work. He also provided a typically Jamesian wide-ranging and eclectic overview of the historical source material for the site, drawing on Classical texts as well as medieval and post-medieval travellers’ stories. The final results were jointly published by James, Gardner and Hogarth in the Journal of Hellenic Studies, a series edited by Percy Gardner.

It is intriguing that despite his engagement in Classical archaeology through his involvement with the Pylos excavations, his role as Assistant Director of the Fitzwilliam Museum and, by no means least, his education at Cambridge, that so little evidence of this makes its way through to his published ghost stories. Neither, despite, his friendship with the Lubbock’s does any evidence of an interest in prehistoric archaeology beyond a passing reference to prehistoric flints in a View from a Hill.

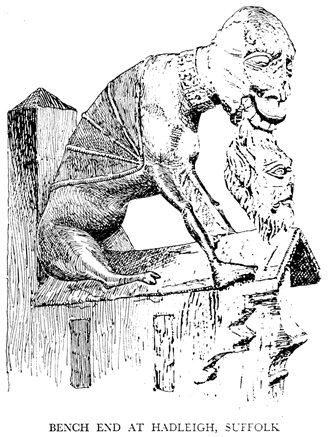

However, when it comes to medieval archaeology and physical remains, it is a different matter, both figure in the bulk of his academic work and his ghost stories. Despite being primarily remembered as a textual scholar, James’s research was not just dominated by an interest in producing edited texts, but also cataloguing – this meant engaging with all aspects of the manuscript- not only its content, but also its physical appearance (i.e. illumination and marginalia) and provenance – in this respect it was as much an archaeological and art historical endeavour as a purely textual pursuit. In particular his fascination with hagiography and apocrypha intersected and fuelled a fascination for understanding and unpicking medieval iconography.

Surprisingly, at the age of 30, when the Disney Chair of Archaeology became empty, Monty gave serious thought to applying for it. His writings when thinking of applying and his application to the Vice Chancellor give a clear understanding of his perspective

“My object in all has been to trace, so far as I could, the historical development of sacred art from the point of view of selection and treatment of subjects, and to bring it into connexion with the literature and legends to which the artist had access/ In other words, I have worked with the view to applying to Christian art those methods which are applied nowadays to the remains of classical sculpture and painting”

“During the last twelve years I have accumulated a very large mass of materials illustrative of Christian art and iconography. This material consists in the main of descriptions as full and accurate as I could make them, of sculpture, painted glass, pictures and illuminated manuscripts existing in a very considerable number of English and foreign churches, libraries, galleries and museums..”

This in fact fits in nicely with some of the important work done by earlier Disney chairs. The outgoing Professor George Forrest Browne had made a special study of runic stones, and published The Ilam Crosses (1889) and The Ancient Cross Shafts of Bewcastle and Ruthwell (1917). An earlier chair, Churchill Babington, had also contributed articles on medals, glass, gems and inscriptions to the Dictionary of Christian Antiquities.

What is surprising though in Monty’s unsuccessful application was how little he had published on topics even broadly related to medieval archaeology or art history. Whilst the modern publication requirements for an academic clearly did not apply in later 19th century Cambridge, this is a little disconcerting. It is hard not to draw notice to the thoughts of Parkin’s in Oh Whistle when he discovers the Templar Preceptory: ““Few people can resist the temptation to try a little amateur research in a department quite outside their own, if only for the satisfaction of showing how successful they would have been had they only taken it up seriously. Our Professor, however, if he felt something of this mean desire, was also truly anxious to oblige Mr Disney”

In fact it was in 1892, the year of his unsuccessful application, that he made his first foray in text in church archaeology despite the fact that he had been clearly exploring church art for a long time. The subject was the sculpture on the Lady Chapel at Ely Cathedral- he had declared an intent to write a monograph on this following an undergraduate visit, but it clearly took him a long time to work up to it. The sculptural programme, heavily defaced by Protestant iconoclasm, was poorly understood. Drawing on his knowledge of apocrypha he identified the programme and read a paper to the Royal Archaeological Institute in August 1892- this was subsequently published in the Archaeological Journal, and then reworked as monograph.

Whether or not provoked by his failed attempt at the Disney Chair the 1890s and early 20th century saw Monty issuing a series of papers on topics related to church art – particularly glass and wall painting- and all with a strong element of iconographic analysis – obviously recalling the detective work of the Reverend Somerton on deciphering the message in the stained glass from Steinfeld Abbey in the Treasure of Abbot Thomas. Most of this work was published in the Reports and communications of the Cambridge Antiquarian Society– of which James was a committee member until around 1910. Unlike many of local archaeological journals, due to its University connections the Reports and Communications had a far wider purview publishing on a wide range of international topics. For example, the 1903 volume which contained a paper by James on French tapestries, also include articles on Irish folklore, Roman Britain, Aztec civilisation, Estonian harpoons, and the ruins of Rhodesia. In addition to publishing papers, he read many more to the society which were not published- sometimes two on one night.

His involvement with the Society was important as it meant he was mixing with other important archaeologists in Cambridge and beyond- including the Disney Professor. He also saw papers read by key figures in the developing world of medieval archaeology, such as W St John Hope, with whom he later collaborated and Frederick Bligh Bond, the notorious archaeologist and psychic whose research at Glastonbury, was he claimed, steered by his spiritualist contacts with a medieval monk of the abbey, and ultimately led to his dismissal from the excavation committee- one wonders whether the conceit of using psychical powers to see the past partly inspired a View from the Hill.

In 1901, there were plans to bring relics claiming to be the bones of St Edmund to the newly constructed Catholic Westminster Cathedral. James, along with others, wrote to The Times arguing that the provenance of these items was dubious in the extreme. Whilst some of the correspondent appear to have had a confessional perspective, James simply took issue with the use and abuse of historical records.

It is not clear whether directly or indirectly provoked by this debate, excavations took place in the chapter house at Bury St Edmunds, with which MR James became involved. This resulted in the discovery of a series of burials which James, using textual sources identified – this fulfilled his predictions laid out in an 1895 monograph on the church in which he suggested

“…if a systematic excavation could be undertaken, as a result of the publication of this book, I should be better repaid thereby for the pains I have spent upon it than by any other means … From the lie of the land I am inclined to believe that much of the crypt would be discovered, and that the sites of the Abbots’ tombs in the Chapter-house (including that of Abbot Sampson) might be ascertained (James 1895: 115).”. Following the excavations, he wrote to The Times re-iterating this identification- although this led to an anonymous rebuttal, also in the Letters page, followed by further support from elsewhere. Whatever the final conclusions, it is clear from the correspondence that he was not present during much of the actual excavation.

James was then again involved in a burial excavation in 1910, when the remains of Henry VI were investigated in St George’s Chapel in Windsor. This was led by W St John Hope, indefatigable excavator known for his “ungentlemanly burrowing” and his “robust” excavation techniques, who James knew from his Cambridge Antiquarian Society days. James was present in his capacity as Provost of Kings as a representative of the two colleges founded by Henry VI. The published description of the opening of the unmarked tomb in the presence of several officials, the cathedral architect and verger again calls to mind the opening of the mysterious tomb in An Episode of Cathedral History probably written a couple of years later in 1913.

Throughout his later life James continued to write about church art and archaeology although after 1910 he mostly stopped publishing in the Cambridge Antiquarian reports and communications. Instead he published his work as small monographs, such as his work on the sculptured bosses at Norwich cathedral , or in the Cambridge Review – as well as regularly writing to the The Times. He also increasingly published in the journal of the Walpole Society a new body established in 1911.

In some case, he revisited work he had previously explored- most spectacularly in the case of the Eton College Chapel wall paintings; as school boy he had spoken in a debate declaring the destruction (as it was then though) of the paintings was ‘among the worst crimes of the century”- he had also given a paper on them in 1894 to the Cambridge Antiquarians. Finally after WWI as Provost of Eton he was able to effect the removal of the stall revealing the surviving paintings. Other work published on wall painting was done in collaboration with EW Tristram, who had been closely involved with the restoration of the Eton paintings and shows James willing to collaborate with talented younger scholars.

A final aspect of his archaeological publication are his two more popular guides- Abbeys (1926) and Norfolk and Suffolk (1930). Abbeys was a publication by the Great Western Railway and intended to help promote tourism within Britain. Both are extensively illustrated with line drawings and photographs and clearly aimed at the popular reader, and so untypically for James, there is very little critical apparatus. Instead as he willingly acknowledges he draws on his own notes, experiences and general guide books (although he does not mentioned the Bell’s Guides which get name checked in. In the short bibliography in Abbey’s he does mention antiquarian works, as well as work by colleagues and acquaintances such as Bligh Bond on Glastonbury. Whilst not academic publications they clearly key in James’ own fondness for church visiting and ecclesiology which went back to his boyhood. If not labours of love, they certainly can be seen as a contribution to the wider, more popular literature aimed at the interested amateur which James himself regularly used on his visits in Britain and beyond

To conclude- it is clear that James was engaged and informed by archaeology and archaeologist over his career. His academic research, something that Pfaff’s biography goes into in far greater depth, is at the intersection of palaeography, history, art history and archaeology. Despite his brief excursions into Classical archaeology as a young man, his engagement with the material remains of the past is solidly rooted in the medieval world. At its heart is a very text-led conviction that a thorough grasp of the textual sources – whether part of the cannon or more apocryphal or esoteric- is at the heart of the interpretation of medieval ecclesiastical decoration. Within the fairly limited scope of his archaeological work, figurative representation in ecclesiastical contexts, he was doubtless correct. He never attempted to move beyond the text, to address imagery in its own terms or widen his interests more widely into the study of military or economic history and archaeology.