At last some good news about Bletchley Park, where Allied codebreakers worked in World War II. Its a fantastic site, but has been badly in need of investment to keep it standing. Whilst the house itself is in good nick, the huts are in pretty poor shape (somewhat inevitable as they are mostly pre-fabs which were never intended to have a long life). Its well worth a visit; many of the guides worked at Bletchley during the War. Its great that EH has finally provide some money for this site; I’m amazed that given its importance during the War and its key role in the development of computing technology that its had to struggle so hard for funds.

Rotherwas encore

More news about the Rotherwas Ribbon

A Land

I’ve just finished reading Jaquetta Hawkes’ wonderful book ‘A Land’. Written in the late 1940s, it is a meditation on geology, archaeology and the development of Britain. Hawkes was that rare thing, an archaeologist who could write wonderful prose, in places coming close to poetry.

It is this immense antiquity that gives our land its look of confidence and peace, its power to give both rest and inspiration. When returning from hill or moor one looks down on a village, one’s destination, swaddled in trees, and with only the curch tower breaking the thin layer of evening smoke, the emotion it provokes is as precious as it may be commonplace. Time has caressed this place, until it likes comfortably as a favourite cat in an armchair, also caresses even the least imaginative of beholders.

Like many of the writers I’ve been reading recently, Hawkes takes an unashamedly (Neo-)Romantic view of the landscape; she quotes extensively from Wordsworth and illustrates the book with a sketch by Ben Nicholson . Like W. H Hoskins she looks back to the period between the end of the Middle Ages and before the Industrial Revolution as a ‘Golden Age’ of English landscape, and, again like Hoskins, she revels in the immense regional variation within the British landscape (though unlike Hoskins her perspective is truely British rather than English). It is a useful counterpoint to the other book I’m reading at the moment Matthew Johnson’s Idea of Landscape which emphasises the English landscape archaeology tradition in general, and (in Johnson’s view) its founding father, WH Hoskins, firmly in an intellectual tradition that stems from 18th century Romanticism (and Wordsworth in particular). He clearly dislikes Romanticism in all its form seeing it as the progenitor of (in his words) ‘dreary, dreadful, Victorin mawkishness’, and I think his aesthetic tastes (he prefers the salty, roaring, bawdy 18th century) are perhaps clouding his judgement of later writing and scholarship on the English landscape. Though perhaps I’m letting my preference for the Romantic and particularly Neo-Romantic vision of England cloud mine.

postscript: despite my preference for Romanticism I can’t stand Wordsworth (I blame A levels for this)

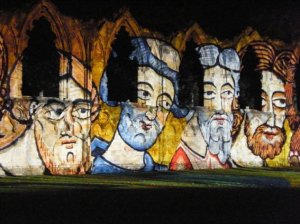

York lightshow

Heartbreak Hill

Made a visit to the site of Heartbreak Hill, an allotment scheme created for unemployed ironstone miners just outside the village of Boosbeck. It was set up in the 1930s by Rolf Gardiner (see postings below) At this time, unemployment in this area was even higher than in other areas of the norht-east such as Jarrow Land was given for the allotments by Colonel William Wharton, owner of Skelton Castle. Students were brought in to help clear the land of roots and stones. This student element and the artistic / utopian ideals of Gardiner meant that there was also a strong artistic element including operas (one of the volunteer students was the composer Sir Michael Tippett), folk music and dancing.  The allotments are still there; unlike many municipal allotments, the plots are clearly marked with fences and boundaries and many are still in use. Also plenty of livestock, including chickens, pigeons and a goat. Not clear how many, if any, of the sheds and pigeonlofts are original, though I spotted at least one re-used Anderson Shelter.

The allotments are still there; unlike many municipal allotments, the plots are clearly marked with fences and boundaries and many are still in use. Also plenty of livestock, including chickens, pigeons and a goat. Not clear how many, if any, of the sheds and pigeonlofts are original, though I spotted at least one re-used Anderson Shelter.

Chagos reversal

Shockingly the Law Lords reversed an earlier judgement that the deported population of the Chagos Islands could return to their homeland. Between 1967 and 1971 they were illegally removed by the British government so that the island of Diego Garcia could be handed over to the US as a major airbase. Most islanders went to Mauritius, but some came to the UK. Whilst some don’t want to return others are keen to do so, and have been finding a long campaign to be allowed back. In 200o the then Foreign Secretary accepted the result of a court case saying they could return, but in the fallout of 9/11 US security paranoia led to pressure being placed on the UK to change their policy and contest the Chagossians right of return. The islanders continued to take their fight through the courts and the UK government has consistently opposed them, despite admitting that the way they were initially treated was wrong. The government fought their case on the basis that resettlement would be a security risk to the US airbase and the cost of resettlement would be too costly. Both these arguements are profoundly flawed. The islanders are not demanding to be allowed to reoccupy Diego Garcia (DG), just the outer islands. It is hard to see how they can form any kind of security risk; if the US are unable to contain any potential threats from 150 impoverished Chagossian thinly spread across a isolated islands some over 100 miles from DG, then one wonders how they expect to be able to fight global terrorism. They don’t seem too worried about locating their Guantanamo Bay prison home to many hardened terrorists (hem hem) on Cuba, on an island controlled by a Communist administration with a history of ‘difficult’ relations with the US. The cost of resettlement needn’t be an obstacle either. A report has shown that there this would be a feasible process. The former main crop of the island was copra, and there are many abandoned palm plantations scattered across the islands which could be used to produce palm oil, whilst there are good fisheries offshore. Combined with a carefully developed eco-tourism industry (the area is rich in wildlife) it could easily be economically viable for the small population. (see here for the Chagos Conservation Trust’s critical but constructive comment on the Howell Report).

The Chagossians will take the case to the European Court of Human Rights but it is difficult to feel optimistic. What is so depressing is that even through the UK government admit that the original removal of the population was manifestly unjust they refuse to do the decent thing and let the islanders return, and instead defer ironically to the security demands of the so-called war on terror. All in all, a shameful and squalid affair back in 1967 and a shameful and squalid affair today.

Hackney Library Ban

A rather depressing little story about the writer Iain Sinclair being banned from launching his new book at Hackney Library

Watkins and Crawford: Photographic perspectives

More ley lines….quite literally. Kitty Hauser’s book on O.G.S. Crawford touches on his tetchy interactions with Alfred Watkins, the promoter of the notion of ‘ley lines’. As founder and editor of Antiquity, Crawford gave such ‘crankeries’ pretty short shrift. However, they both shared an interest in the importance of photography in the study of the past. Crawford, as an innovator in aerial archaeology, and Watkins as significant photographer in his own right and a member of the Royal Photographic Society. However, the cartographic nature of the vertical aerial photograph contrasts strongly with the ground level view of Watkins work, much of which he used to illustrate his published work on ley lines. This difference closely reflects the difference approaches to landscape explored by writers such as Chris Tilley (in his Phenomenology of Landscape). Not surprisingly in Tilley’s work he criticises the ‘objective’ and ‘totalising’ objective and map centred approach which characterises much modern landscape archaeology, instead privileging the subjective, experiential and phenomenological perspective used by many post-structuralist archaeologists and anthropologists. It seems that that despite Watkins’ approach being consigned to the dustbin by Crawford, it is in fact his approach that is more in tune with certain streams of modern archaeology. Poor old Crawford also comes in for a bit of a kicking in Matthew Johnson’s Ideas of Landscapes. However, I think Tilley’s book certainly over-does his arguements and his heavy use of binary oppositions in contrasting objective/subjective approaches to landscape are a little surprising in someone who is meant to be post-structuralist. I’m going to go back to Matthew Johnson’s book soon, in the light of my increased interest in the uses of archaeology in the 1920s-1950s (and the fact that I read it when getting an average of four hours of sleep a night); now I’m more awake and more informed I’m looking forward to giving it another go.

Rotherwas Resurgat

I’m pleased to write that reports of the redating of the Rotherwas ribbon are much exaggerated. I’ve been contacted by Keith Ray, County Archaeologist for Herefordshire who has let me know that contrary to my earlier post the C14 dates and finds information are all pointing to a Late Neolithic/Early BA date for this highly interesting and unusual site. There will be more information appearing on the Herefordshire SMR website as it becomes available.

Pater Noster

I was at a wedding this Saturday. During the service, the Our Father was said. It was rather disconcerting to notice that looking round the church barely anyone under 40 was joining in with it. If I was charitable I’d say it was because they were shy, but I think it was more likely to be that they simply didn’t know it; something I found highly depressing. Knowledge of basic prayers and the broad shape of the liturgy and the liturgical year ought to be a fairly fundamental part of people’s general knowledge.

This kind of knowledge is not something that should only belong to practicing Christians. For anyone with an interest in history, literature or popular culture, a basic understanding of the tenets of Christianity is essential. People need not believe in it, but they should at least grasp the basics as part of their basic general knowledge. How can people understand huge chunks of British, European and World history, art and literature without appreciating a key aspect of the social context in which it was created? This applies to everything from Shakespeare, Chaucer and James Joyce through Da Vinci, Millais, Chagall and Stanley Spencer to Father Ted and the video of ‘Like a Prayer’ by Madonna.

When teaching medieval archaeology I can no longer assume even a basic knowledge of Christianity, and have to provide crib sheets to basic concepts such as the Eucharist and the Passion. This is not a call for increased belief in (I’m a lapsed Catholic- though not so lapsed I don’t feel guilty about it), but a knowledge of a key strand of the European cultural inheritance.